The real gamble is playing the same game as your competitors

by Bruce Tait, for Journal of Brand Strategy • Published January 2021

Abstract

The essential task of strategy—particularly brand strategy—is to differentiate. But it can go wrong in many ways as managers and strategists are drawn inexorably back to category conventions. This paper argues for a more dedicated focus on differentiation and outlines important observations regarding the challenges inherent in defining such a brand strategy. It will examine a case study about successfully breaking category conventions and some principles and lessons to help the practitioner stay on course.

BREAKING FREE OF CATEGORY CONVENTIONS IS NOT SO EASY

For the past 20 years, Tait Subler has worked with organizations and brands around the world to fundamentally rethink how their brands are positioned in the marketplace. A client team setting out to define and successfully activate a new brand strategy typically acknowledges that the new strategy must articulate how their product or service is different from the competition. Despite this intention to set brands apart from the competition, powerful countervailing forces often cause well-meaning and talented teams to reiterate the dogma of their category rather than articulating a truly differentiated original idea within the new strategy. Interestingly, the allure of generic category benefits seems equally powerful for seemingly ‘creative’ or iconoclastic business cultures as it is in more traditional and conservative organisations.

The same strong gravitational forces pull brands back to debilitating sameness across countries, cultures and categories if those forces are not properly identified and explicitly addressed as the new strategy is being developed.

The brand differentiation challenges facing marketers have been evident for a long time. Back in 2006 a Copernicus/Greenfield Online study showed that in 48 of 51 product and service categories, consumers perceived the leading brands as becoming more similar over time. According to AC Nielsen BASES, 93 per cent of estimated all-new consumer products fail within the first three years. Lack of differentiation is the leading reason for failure(1).

This paper is intended to share observations as to how category benefits and category conventions too often usurp fresh insight and ideas when a brand strategy is defined, redefined or refined. It will also offer some principles and approaches Tait Subler has employed to fight this self-destructive march towards sameness. Both the challenges and the solutions will be illustrated through a case study from the US casino category—Chumash Casino Resort, in California.

DIFFERENTIATION CANNOT BE TREATED AS JUST ONE OF MANY GOALS FOR A BRAND STRATEGY

The seminal work of academics like Theodore Levitt and Michael Porter at Harvard Business School have reinforced the importance of differentiation in managers’ minds for a long time. Accepted tools of brand measurement like Y&R’s Brand Asset Valuator serve to reinforce the importance of differentiation because it figures prominently in their model. The strategic importance of differentiation is neither novel nor contentious.

The problem is that differentiation is usually just one item on a much longer list of goals for the brand strategy, leading to a false equivalence for all the goals and a diffusion of focus. For instance, management typically wants the brand strategy to be ‘relevant’ (although to whom it is to be relevant is not always clear), ‘ownable’ and ‘competitive’. The effort to be more competitive leads to a lot of benchmarking analysis. How does everyone else do everything? Of course, the problem with a focus on competitors is that you become more and more like them. In his Harvard Business Review paper ‘What is Strategy?’ Michael Porter acknowledged that ‘… the more benchmarking that companies do, the more competitive convergence you have – that is, the more indistinguishable companies are from one another’(2). In an effort to be more ‘competitive’, companies are undermining the one thing that can create sustainable competitive advantage—differentiation.

In that same paper, Porter identifies being different from your competitors as the very essence of a strategy. It is not one of many ways to think about what the strategy ought to do … it is the whole point of strategy. Porter’s perspective is that a business has competitive advantage over its competitors in two ways—cost advantage and differentiation advantage. Cost advantage is the route to success for commodities. But the very concept of a brand is to distinguish the product or service from generic offerings to create rational and irrational preference or loyalty, which in turn sustains pricing power, improves margins and creates a sustainable competitive advantage. In Porter’s words, such advantage can only be created through a strategic positioning that works by ‘… preserving what is distinctive about a company. It means performing different activities from rivals…’

Market researchers can fail to point out the more foundational role of differentiation in their reports. Scores for relevance, differentiation, etc. are often treated equally. Compounding the problem, differentiation can be difficult to measure. It is often based on emotional and values-based connections (non-functional differences) that are difficult to surface in quantitative research.

DIFFERENTIATION IS THE HARD PART

The greatest risk of adding ‘differentiation’ on a longer list of goals for brand strategy is that it lets the team defining the brand strategy off the hook. Focus can shift to other seemingly reasonable goals that are usually easier to address. For instance, ‘relevance’ has become a big concern for many mature brands.‘How can we stay relevant with this new generation of Millennials (or Gen Z)?’ That question is quickly followed by ‘how are others in our category doing it?’ Often the same narrative born of stereotypes and assumptions about an incredibly diverse population is then used by everyone in a category to ensure their relevance (and sameness).

Relevance becomes a reasonable concern for mature businesses in fast-changing categories when new competitors and technologies emerge. But how many elegantly stated bromides posing as strategies have been rationalised as being ‘highly relevant’? When pressed, the lack of differentiation in these strategies is usually kicked down the road . . . ‘we’ll address it in execution.’ A generic brand strategy, however, cannot be saved in execution. Doing the same thing better is a momentary advantage at best. Operational effectiveness without the guidance of an overarching, differentiating strategy devolves into reactionary tactics. Competitors will copy the tactics quickly, and any advantage quickly evaporates. To Porter’s point, if the brand strategy is not differentiating, it fails the acid test for being a strategy at all.

Of course, brands do need to be relevant in the way they differentiate. Being different in an irrelevant way misses the point. But relevance too often becomes the single biggest crutch for a team that has not uncovered an original consumer insight or developed an idea on which to base a unique brand strategy.A differentiated strategy often involves a creative leap. New narratives are needed that uniquely fit with consumer needs and the possibilities for their product or service. Data and insights need to be synthesised in new ways. It is hard, but it is the very essence of strategy. That is why differentiation has to be the primary focus for any team that hopes to actually make it happen.

BEWARE THE ‘ZAJONC TRAP’

The renowned Stanford and University of Michigan psychologist, Robert Zajonc, studied and wrote about the Mere-Exposure Effect, where people tend to like or prefer things more when they become more familiar with them(3). His findings provide a very strong explanation for the underlying psychological challenge we face when trying to forge a differentiating brand strategy. It seems we are all hardwired to prefer things we know over things that are new. This may reflect some evolutionary benefit to avoiding strange new foods or animals that could end a life before one’s genes could be passed on to the next generation. The ramifications of Zajonc’s insights are highly consequential for brand strategy. We know that a unique and different brand strategy is vital to create sustainable competitive advantage, but everyone (management, consultants, agencies and consumers) will initially balk at the new versus the conventional. This is what we call the Zajonc Trap.

Once we understand that humans are biased towards the known and familiar, then the decision dynamic within an organisation becomes easier to understand. Everyone will feel uncomfortable with any hypotheses and ideas for a brand strategy that do not fit with well-established category benefits. There will be a strong, unstated and irrational preference for undifferentiated brand strategy options, precisely because they are so familiar.

Importantly, consumer research will suffer from this same innate bias towards the familiar. Consumers will gravitate towards strategic ideas that reflect what they see in the category already. As a result, there is less likelihood that a unique and differentiating strategy recommendation will have definitive market research evidence on its side. Not surprisingly, few managers feel confident pushing an idea up the ladder without strong black and white research findings to support it. And senior management (being human) will have an irrational and unstated preference for a brand strategy that is more familiar. All of this makes the recommendation to proceed with a differentiated strategy risky to one’s career. Professor Zajonc helps us understand just how perilous it is for a differentiating strategic idea to survive.

Typically, the Zajonc Trap leads to a process of negotiation and rounding off of distinctive edges until everyone is more comfortable supporting the (now less differentiating) strategy. Unless everyone is alerted to their innate preference for the familiar, this unconscious process of consensus building can seriously neuter a brand strategy.

THE SPOILS GO TO THE BOLD (IF THEY KEEP THEIR JOBS)

The average tenure of a CMO at 100 of the top US ad spenders recently slipped to 43 months, less than half that of a CEO(4). It is a difficult and insecure position in many companies, and therefore takes real courage to recommend a brand position that is outside the normal category conventions. For too many, the safer path is to simply aim for strong execution of a relevant but well-established category benefit. And it is rare to find a CEO or board that is pushing for real differentiation.

There is a paradox here; medium to long-term success depends on brand differentiation, but in the short term it may seem safer and wiser for management to avoid the risks of pushing a strategy that strays outside category norms. Successful brand strategies will become less of a highwire act only when senior management and boards better support the imperative to differentiate—making category benefit strategies riskier to careers than noble failures that at least try to differentiate. Start-ups have it easier on this front. They are expected to have a different idea—and the successful ones do.

Entrepreneurs have a passionate belief in the big idea that makes their product, service or brand different from everything that has come before. They attract investment from other true believers. That helps explain why the brand that turns a category on its head usually does not come from the incumbent category leaders.

SAMENESS OFTEN STARTS WITH CONSUMER SEGMENTATION

Our clients facing differentiation challenges have usually adopted (implicitly or explicitly) a model for thinking about consumer segments that is common to the category. Gucci used a model that effectively had all its competitors targeting the same segment. By introducing a new segmentation model, Tait Subler could identify a market and positioning white space for the brand. Red Wing Shoes (the now trendy work boot) segmented the market that put all the competitors at the centre of the x/y axis they used to define four important segments. In effect, all the brands were trying to be everything to everyone. A new segmentation model helped find an aspirational badge in a category that had previously positioned on functional product benefits. In both these cases, the road to successfully articulating a truly differentiating brand strategy started with rethinking what the important dimensions of segmentation really were.

In some cases, we find clients who have segmented the wrong thing. Typically, we segment types of people, but there are many categories where an occasion-based segmentation (sometimes called a need-state segmentation) makes more sense.

Such was the case in the American beer category in the 1990s. Most beer brands used a segmentation of drinkers, but drinkers were increasingly using a portfolio of brands for different occasions. For instance, they might drink one beer while sitting at home watching a game, another at a club and yet another when they wanted to impress a date. Corona beer recognised this occasion-segmentation model early on and grabbed tremendous share from the traditional light beer titans in the US market by owning the ‘relaxation beer occasion’. This occasion transcended all types of beer drinkers and exposed a huge market for them. The relaxation moment also fit their provenance on the beaches of Mexico. At the time, incumbent competitors like Miller Lite could not see this opportunity because they were using the wrong segmentation model (of people) rather than occasions.

We find many categories where occasion segmentation makes more sense. While a ‘people’ segmentation makes sense for dog food because a person’s (relatively static) attitudes towards pets drive brand selection, pet treats are more dependent on the occasion. Tiny bits for training, big slow chews when guiltily leaving for work in the morning. The occasion or need state dictates the product form and brand selected more than the type of pet owner you are.

VERTICAL INDUSTRY EXPERTS REINFORCE CATEGORY CONVENTIONS

Group think is perhaps the most obvious reason that categories have brands with similar brand strategies. Consultants with deep and long experience in the category are hired by management teams to help craft the brand strategy. These are companies who want someone who is up to speed—someone who will know what is relevant in the category. It is hard for anyone who has spent a career in one category to bring fresh ideas to the table. The team developing a differentiating brand strategy must be a healthy mix of deep experience and outside perspective to ensure the output is both relevant and differentiating.

A CASE STUDY IN ZIGGING: CHUMASH CASINO RESORT

When most people think about casinos and gambling in the United States, they think of Las Vegas. Sin City. A place to drop your inhibitions and imbibe the excitement and vaguely dangerous opportunity to gamble, drink and party. Most assume the biggest, most successful casinos are situated in Las Vegas, but that is not the case. The largest casino in the world resides in Thackerville, Oklahoma, where Native American gaming thrives. In fact, Native American gaming operations dominate the list of the top 10 casinos in the US, and California is home to 2 of the largest—Pechanga Resort & Casino and San Manuel Casino (near Los Angeles (LA))(5). This is big business in terms of both gambling revenues and profits. These giant operations offer Californians the thrill of Las Vegas without the distance. San Manuel’s ubiquitous TV commercials use the tagline ‘All Thrill’ with high-gloss, effect-laden advertising to draw in LA gamblers hoping to win big and party hard. They offer Las Vegas closer to home.

In this environment, the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians operated Chumash Casino Resort, located half an hour north of Santa Barbara and 125 miles north of LA. Chumash Casino Resort had prospered by using category conventions. They found success selling generic gambling for the local market because they were the only game in town. Over 20 years, the relatively small casino grew from tents offering bingo to a luxurious hotel and complete casino offering. Bill Peters, the general manager, called their category-benefit strategy ‘win and grin’. The core brand strategy was punctuated by constant promotions and give-aways as well as entertainment in their show room. The problem? While the beautiful Santa Ynez Valley is a wonderful location, the Santa Barbara area lacked the population base to grow the business much further, and revenues plateaued by 2014.

That is when Chumash Casino Resort management decided to audaciously expand their market towards LA, running into direct competition with the mighty San Manuel Casino. Chumash Casino Resort would need to convince gamblers from LA and Ventura Counties to make the trip to Chumash Casino Resort. And for the first time, they would not be the only game in town. Chumash Casino Resort would have to differentiate its brand of casino resort from San Manuel and other casinos closer to the LA market.

The approach

Tait Subler worked with the management team and ownership at Chumash Casino Resort to develop a new brand strategy that would make relevant differentiation from San Manuel its singular goal (not one objective among many). This clarity and focus regarding differentiation provided a tremendous advantage as we set out to define a successful strategy. Management needed to define a different point of view about gambling that Chumash Casino Resort could own and deliver better than its larger competitor. The entire team bought into this focus before work started.

Tait Subler has found that the primacy of differentiation can be baked into the articulation of the brand strategy. The framework for our strategy statement is based on PayPal founder, and Silicon Valley billionaire, Peter Thiel’s crucial test for judging whether to invest in a start-up, that is, it has to have a different and accurate belief about the category (casino gambling in this case) that separates it from all other competitors(6). In this model, the crux of a brand strategy is not just a positioning, but a Strategic Point of View. The strategic challenge can therefore be framed as being about defining ‘X’ and ‘Y’ in the following statement:

All our competitors believe gambling is about ‘X’, but we believe gambling is really about ‘Y’ . . . And that’s why we do these things differently and communicate to our guests in this (different) way.

Tait Subler engaged all the stakeholders at Chumash Casino Resort in a journey to identify their most powerful difference versus San Manuel and other competitors closer to LA. Then we created hypotheses for a Strategic Point of View and conducted qualitative research with both current guests and prospects in the expanded market to their south.

Our open-ended research process allowed us to understand how consumers viewed the competitive brands and Chumash Casino Resort. But, most importantly, we were able to delve into the ‘ideal gambling experience’ for these people. That led to a couple of revelations. Firstly, the ideal gambling experience was different depending on the day (or night). They had different occasions for gambling, and different need states were fulfilled on different occasions. Sometimes they wanted the adrenaline and excitement that was at the centre of virtually all casino advertising (remember San Manuel’s ‘All Thrill’ tag line). But often they sought another feeling entirely—relief from the stress in their lives.

One respondent summed up the ideal gambling experience this way:

I’m in my bubble, it’s me time and I can put a barrier between me and the expectations and stress I feel all the rest of the time. I just zone out and I’m lost in the slot machine for a while. For that time I’m playing, I feel free.

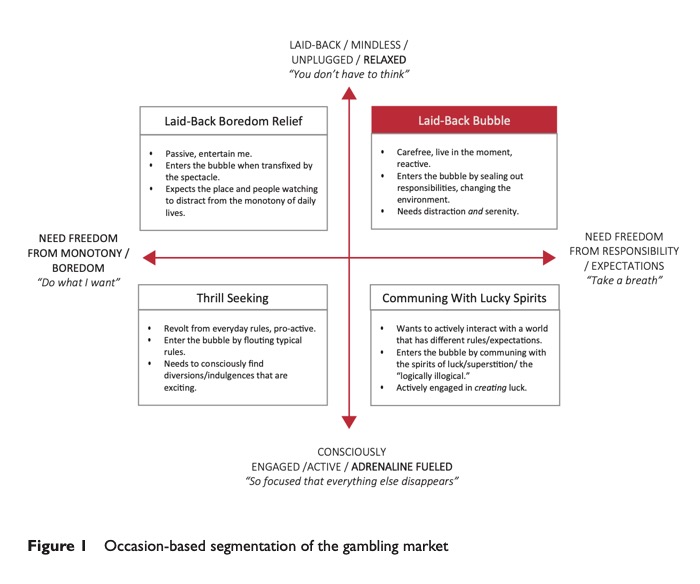

Far from excitement and thrill, this was akin to Corona’s relaxation beer moment in gambling. Our conclusion: an occasion-based segmentation model (Figure 1) makes sense in this category … and all the competitors (category convention) are focused on only one of the occasions (thrill and excitement).

The second insight to emerge from this research was that Chumash Casino Resort had a valuable and absolutely proprietary advantage in its location. While it might be further away in miles, the drive up the coast and into the Santa Ynez Valley was in itself relaxing compared with the traffic and smog of LA. The drive could also take less time because of less traffic congestion. The expansive, natural beauty of the area, sometimes called Santa Barbara Wine Country, helped gamblers unload their worries and start to enter that bubble we had come to understand. This was encouraging because San Manuel could never imitate this difference-maker. The Santa Ynez Valley was really the Valley of the Chumash.

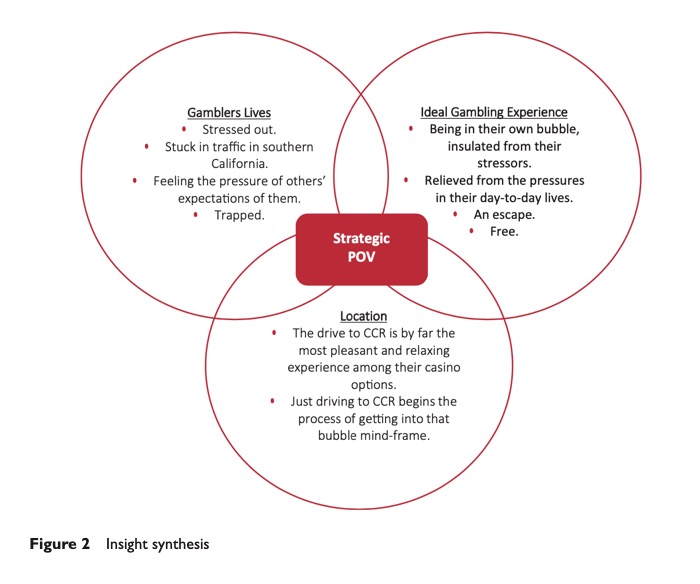

Our learning allowed us to see three important insights (Figure 2) that would need to be synthesised to arrive at a differentiating and relevant strategy, based on real consumer and client insight instead of category conventions.

We conducted quantitative segmentation where we were able to size the four occasion segments in terms of dollar value, percentage of all visits to casinos, etc.

This encouraged us to recommend a Strategic Point of View that would allow Chumash Casino Resort to own the ‘laidback bubble’ occasion. If an LA gambler wanted excitement and a lost weekend of excess, we were not the casino for them that day. But if they wanted a break from their worries—this was the place. This occasion was relevant across demographics. It allowed Chumash Casino Resort to be a unique place, not a ‘Las Vegas Wannabe’, as a respondent called the competitors.

The brand strategy

First we articulated the idea within the Peter Thiel paradigm that contrasted our central belief with everyone else’s belief in this category:

Other casinos believe that gambling is about adrenaline and excitement. But we believe a great casino is about freedom from responsibilities and expectations.

This was stated simply as a Strategic Point ofView that merged our location with the idea of freedom from stress (the ‘bubble’ described by consumers):

You can gamble anywhere, but you can only set yourself free in the Valley of The Chumash.

And that led to a simple tag line for advertising:

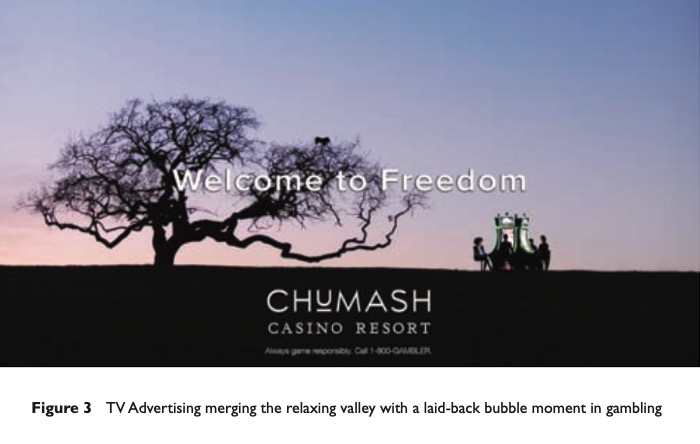

Welcome to freedom

Marketing communications stood in stark contrast to the loud, fast and adrenaline-soaked efforts of San Manuel and others. There was no ‘win and grin’, and it was shot as point of view or from behind models so that it focused on the ‘bubble moment’ rather than a type of person.The parallel between the laid-back beauty of the valley and the sanctuary sought by guests in their gambling bubble was brought to life in unusual advertising that brought gambling moments outside into the nature of the valley (Figure 3).

Investment decisions at Chumash Casino Resort changed. The idea of a club with loud music and high energy was dropped in favour of a laid-back Center Bar. Staff was coached on the simple but profound idea that job #1 was to get people into their bubbles as fast as possible and to make sure that they stayed in their bubbles as long as they wanted. Nothing should irritate them, and they should want for nothing while playing.

Results

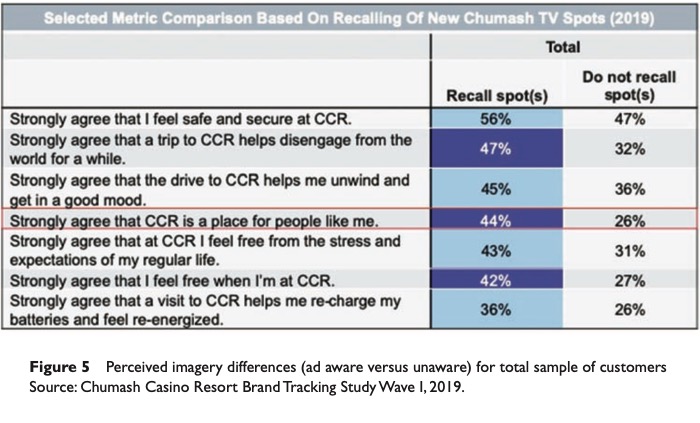

A brand tracking study was designed to measure how well Chumash Casino Resort was taking ownership of this laid-back bubble moment in the minds of gamblers in the expanded and contested market towards LA (Figure 4). The first wave of tracking was fielded after media expenditures had reached only 50 per cent of respondents. This allowed for a great opportunity to see the perceptual differences between those who saw the ads and those who did not (Figure 5).

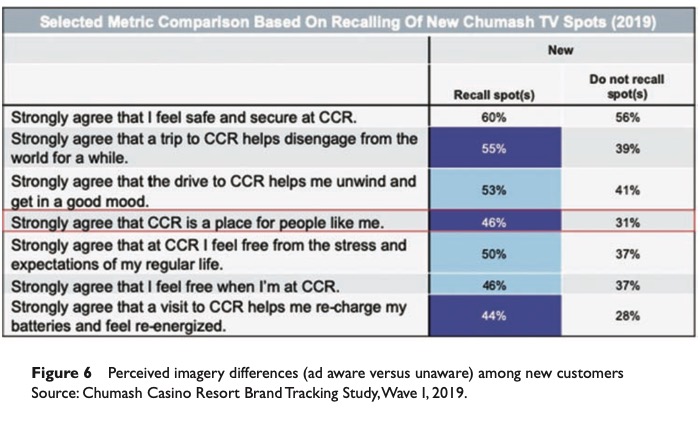

Differences between those who recall the TV advertising and those who do not was dramatic, with 10–18 per cent gaps in strong agreement with the desired brand imagery goals. The team, however, questioned whether those remembering the TV advertising were somehow more passionate, long-time fans of the brand, so the results were more about correlation than causality. To hold the brand to a higher standard, we looked at new guests who had first visited since the ads had been running. The results show that the gaps were equally impressive among new customers. Seeing the TV commercials had a profound impact on expectations and perceptions of this new experience (figure 6). Importantly, the reality of the offering was living up to the expectations set by the advertising. Chumash Casino Resort was delivering on the brand strategy.

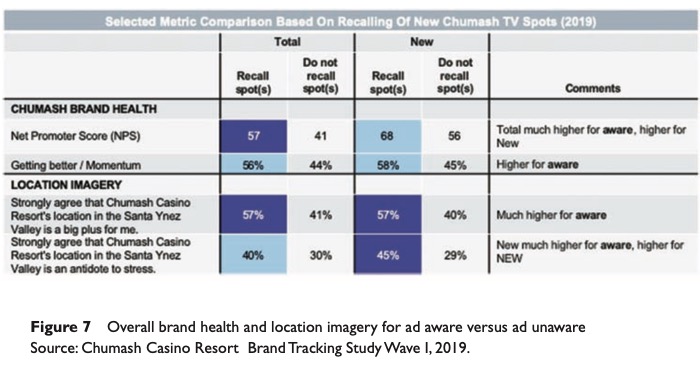

Not only were respondents in the tracking study getting the right message, but the right message was making a big impact on overall brand strength measures like Net Promoter Score and Brand Momentum (brand is getting better, staying the same, getting worse). Further, the goal of leveraging the location and drive was becoming more salient, and we successfully connected it to the idea of being free from stress in this place (figure 7).

The bottom line business results

Business results tell a similar story to the brand tracking. Chumash Casino Resort is experiencing real growth again. Gaming revenue increased by nearly 14 per cent since the new strategy was launched in 2017, and total revenue has increased by 15 per cent in that time frame. Tribal ownership is extremely pleased that casino management dared to break with category conventions to drive this business success. In fact, an important ancillary benefit has been noticed—pride. Employees and stakeholders are rallying around this unique perspective on gambling that reflects the home of the casino and the tribe that owns it. A differentiating point of view allows for consumers and internal constituencies to feel proud of their brand’s differences.

TEN GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR DEVELOPING TRULY DIFFERENTIATING BRAND STRATEGY

Through the work with Gucci, Red Wing Shoes, Chumash Casino Resort and many other clients over the past 20 years, Tait Subler has distilled 10 guiding principles that help to successfully define a differentiating brand strategy:

- Differentiation has to be the primary objective of brand strategy, or it can be brushed aside in favour of easier or more topical objectives.

- Make sure the Zajonc Trap (the inherent bias humans have towards the familiar) is an acknowledged elephant in the room. Challenge every compromise—are we succumbing to the Zajonc Trap here? At what cost?

- Demand that the strategy live up to Peter Thiel’s model—how are we fundamentally different from our competitors? The articulation of the brand strategy should be a point of view that is unique in your category, and it should stand apart without the benefit of execution, as an idea on its own.

- Look for a different way to think about consumer segmentation. Is there another viable or more incisive model that helps identify white space opportunities against previously unidentified segments? (Occasion segments versus consumer segments, for instance).

- Explore types of brand imagery that are unique in your category—if everyone is focused on product imagery, consider brand values/purpose or occasion imagery, for instance(7).

- Keep asking the consumer about the ‘ideal’ brand experience in different ways … is there something there that everyone else has missed?

- Look for thematic parallels between pieces of your strategy puzzle that may not normally go together—in the Chumash Casino Resort case, the relaxing nature of their valley was married to the laid-back stress relief sought in the gambling bubble. Mashups lead to strategic ideas that can be executed in provocative ways.

- Create teams that include deep experience in the category and lateral thinkers who can draw on experience in many categories on your team.

- Senior management needs to free brand managers from the tyranny of category conventions and make the quest for a sustainable competitive advantage paramount. This is an important culture shift for many organisations.

- No, relevant is not enough, no matter how much you all agree on it. It is not really a strategy at all unless it is differentiating.

References and Notes

(1) Clancy, K., Krieg, P. (4 April 2007) ‘Your Gut Is Not Smarter Than Your Head: How Disciplined, Fact-Based Marketing Can Drive Extraordinary Growth and Profits’,Wiley, Hoboken, NJ.

(2) Porter, M. (November–December 1996) ‘What is strategy?’ Harvard Business Review. https:// hbr.org/1996/11/what-is-strategy (accessed February 8, 2020)

(3) Murphy, S.T., Zajonc, R. B.‘Affect, cognition, and awareness: affective priming with optimal and suboptimal stimulus exposures’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,Vol. 64, No. 5, pp. 723–739.

https://doi.org/10.1037/00223514.64.5.723.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14693023_Affect_Cognition_and_Awareness_Affective_Priming_With_Optimal_and_Suboptimal_Stimulus_Exposures (accessed February 8, 2020)

(4) Ives, N. (6 June 2019) ‘Average tenure of CMO slips to 43 months’, Wall Street Journal.

(5) Tripinfo.com, based on total square feet of gaming.

(6) Thiel, P., Masters, B. (2014) ‘Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future’, Crown Business, New York, NY.

(7) Gordon,W. (1999) ‘Good Thinking: A Guide to Qualitative Research’, Admap Publications, Henley-On-Thames.

See All Articles →